ChatGPT Atlas Browser: How AI-First Browsing Could Change the Internet

Explore the ChatGPT Atlas browser and how it differs from Chrome and Safari. Learn what AI-first browsing means for search, research, and the future of the internet.

For most of the internet’s history, web browsers have followed the same basic model. You open a browser, type a URL or search query, scan links, click results, and manually piece together information. Whether you use Chrome or Safari, the workflow is fundamentally the same.

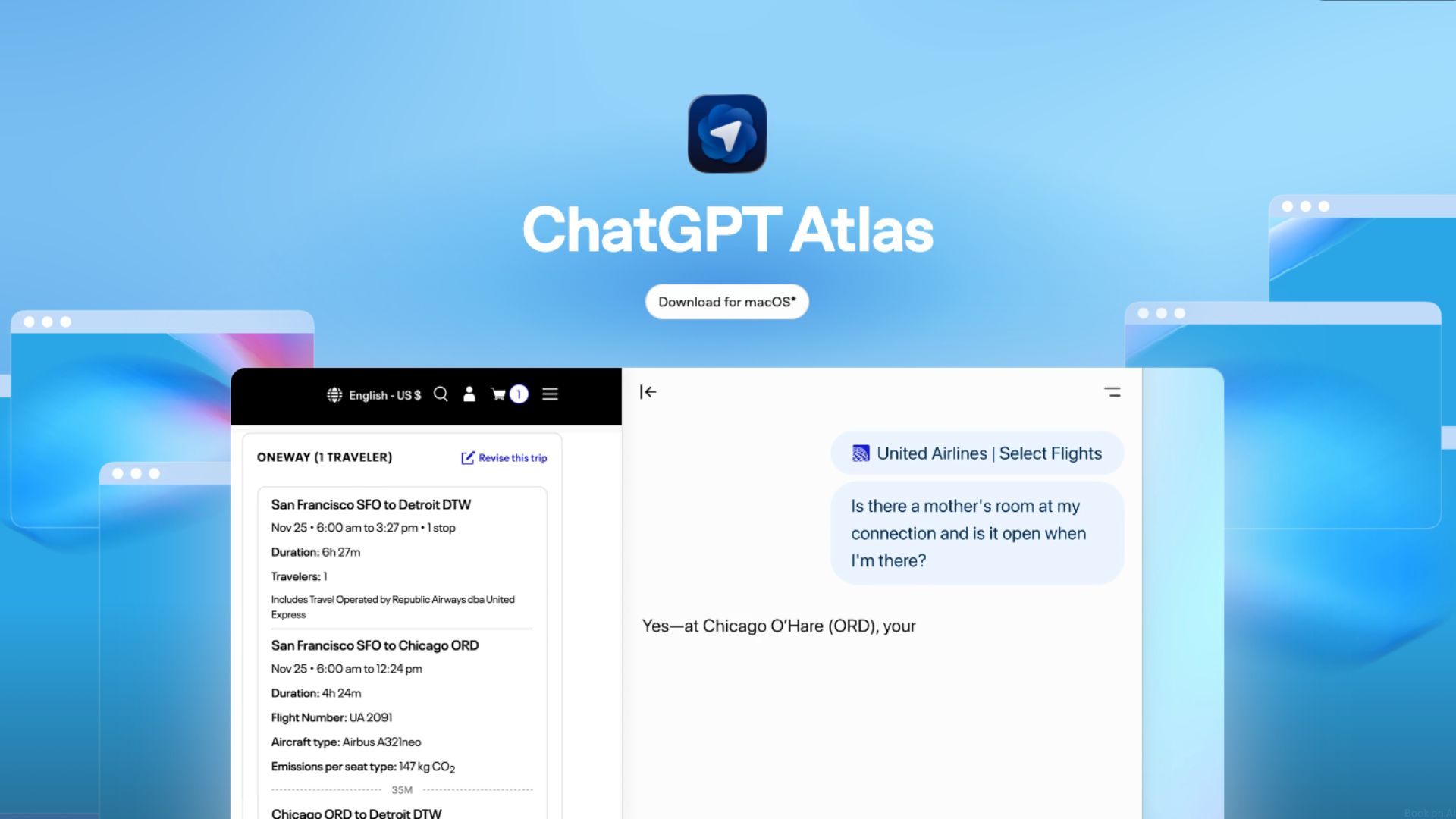

The emergence of the ChatGPT Atlas browser signals a meaningful shift away from that model. Instead of acting as a passive window into the web, Atlas represents an AI-native approach to browsing where understanding, synthesis, and task completion happen inside the browser itself.

This article explores how Atlas differs from traditional browsers, why that difference matters, and what it could mean for how people access information in the years ahead.

What is the ChatGPT Atlas browser?

Atlas is positioned as an AI-first web browser built around large language models rather than tabs, links, and search results. While traditional browsers focus on rendering web pages, Atlas is designed to interpret, summarize, compare, and act on information across the web on a user’s behalf.

Rather than asking “where do you want to go,” Atlas starts with “what are you trying to accomplish?”

The browser is closely tied to ChatGPT and other AI systems developed by OpenAI, allowing users to browse the web through natural language prompts instead of relying on manual navigation.

How Atlas differs from Chrome and Safari

1. From link navigation to intent-based browsing

Traditional browsers such as Chrome (by Google) and Safari (by Apple) are optimized for displaying web pages. They assume the user will decide which links to click and how to evaluate sources.

Atlas reverses that assumption. You describe your goal, such as researching a product, understanding a topic, or comparing options, and the browser actively searches, reads, and synthesizes information for you.

The output is not a list of links. It is an answer, summary, comparison, or action.

2. AI as the primary interface

In Chrome or Safari, AI features are layered on top of the browsing experience. Atlas makes AI the interface itself.

Instead of:

- Searching

- Opening multiple tabs

- Reading long articles

- Taking notes

- Comparing sources manually

Atlas performs those steps in the background and presents a structured response.

This is closer to having a research assistant embedded in your browser than using a tool to view web pages.

3. Fewer tabs, more synthesis

Tabs are a core feature of traditional browsers because they help users manage multiple sources. Atlas aims to reduce the need for tabs altogether.

Because the AI reads across sources simultaneously, users do not need to keep dozens of pages open. The browser aggregates information into a single working context, making browsing more linear and goal-driven.

This is a significant change in how cognitive load is handled during research and discovery.

4. Active evaluation of information

While standard browsers do use complex algorithms to attempt to serve users the most relevant results. They don't completely evaluate credibility, relevance, or consensus. Standard browsers display content and leave judgment to the user.

Atlas introduces a new layer where information can be:

- Summarized

- Compared across sources

- Flagged for contradictions

- Contextualized with background knowledge

While this does not eliminate the need for critical thinking, it changes the default browsing experience from “read everything” to “understand the landscape.”

What this means for finding information online

Search becomes conversational

Search engines are built around keywords. Atlas shifts discovery toward conversation.

Instead of refining search queries, users refine questions. This favors clarity of intent over mastery of search syntax and could reduce the advantage historically held by power users who understand SEO mechanics.

Content discovery becomes indirect

In a traditional browser, users directly visit websites. In Atlas, users may consume information without ever seeing the original page layout, ads, or navigation.

This has major implications for publishers, marketers, and content creators. Visibility may depend less on clicks and more on whether content is selected, summarized, or referenced by AI systems.

Authority and trust signals may change

If AI browsers become common, traditional trust signals like brand recognition or page design may matter less than:

- Accuracy

- Clarity

- Structured information

- Verifiable sources

Content that is easier for AI to parse and validate may have an advantage over content optimized purely for human scanning.

Implications for browsing the web in the future

The browser as an assistant, not a tool

Atlas suggests a future where browsers do more than display information. They help users:

- Make decisions

- Learn faster

- Complete tasks end-to-end

This blurs the line between browsing, searching, and productivity software.

A shift in how websites are valued

If fewer users directly visit websites, value may shift away from pageviews and toward data quality and authority. Websites may increasingly be built not just for humans, but also for AI systems that interpret and reuse their content.

New expectations for speed and clarity

As users grow accustomed to synthesized answers, tolerance for slow, cluttered, or unclear content may decrease. The expectation will not be “find the answer” but “get the answer.”

This could reshape how information is written, structured, and published across the internet.

Is Atlas a replacement for traditional browsers?

In the near term, Atlas is more likely to complement rather than replace Chrome or Safari. Traditional browsers still excel at tasks like running web applications, consuming media, using interactive tools, and doing hands-on development work.

Where Atlas diverges is in how people think while they browse.

For decades, browsing has meant managing complexity yourself: refining searches, opening tabs, skimming pages, and mentally stitching together answers. Atlas challenges that model by treating the browser as an active participant in understanding, not just a passive window to the web.

For research, comparison, and learning, AI-first browsers introduce a fundamentally different workflow. The user’s role shifts from information gatherer to decision-maker, with the browser handling much of the heavy lifting in between.

If Atlas succeeds, the biggest change may not be which browser people use, but what they expect a browser to do. The future of browsing is less about navigating pages and more about navigating ideas.

Frequently asked questions

Is the ChatGPT Atlas browser a search engine?

No. Atlas does not function like a traditional search engine that returns ranked links. It uses AI to search, read, and synthesize information across the web based on user intent.

Will Atlas replace Google Search?

Atlas changes how users interact with information, but it does not eliminate the need for search infrastructure. Instead, it abstracts search behind a conversational interface.

Do websites still matter if people use AI browsers?

Yes, but their role may shift. High-quality, trustworthy content becomes a source for AI systems rather than a destination for human clicks.

Is information from Atlas always accurate?

No AI system is infallible. Atlas can summarize and compare sources, but users still need to apply judgment, especially for critical or high-stakes decisions.

Who benefits most from AI-first browsing?

Researchers, marketers, analysts, students, and professionals who spend significant time gathering and synthesizing information are likely to see the biggest productivity gains.

%20rev.svg)

.jpg)